Use Strong, Unique Passwords

- Passwords are the most common way of proving your identity to access

online services.

- To keep intruders out you should make a different, hard-to-guess

password for each account.

- A password manager helps you create, store and use all these

passwords.

Accounts and authentication

You probably have online accounts with dozens of

organisations, including email and social media platforms, cloud storage and

backup services, financial institutions like banks and pension providers,

and all manner of retailers.

Opening new accounts is a common occurrence — sometimes out of choice, and

sometimes because you’re compelled to as companies and governments move more

processes online.

As a result, more of your private information is stored on computers that

aren’t your own. These computers are called servers or

the cloud, and collectively store information for billions

of people.

This necessitates a way of ensuring that each person’s information is

available only to them. The process of proving your identity to access a

resource is called authentication.

Various means of authentication exist, but the most familiar and still most

abundant is the password. A password is a secret shared

between you and a service you use.

To access the service, you first identify yourself with something unique

but non-secret like your email address, then prove it’s you by

entering the corresponding password. These two bits of information together

are called credentials.

Strong and unique

Criminals attempt to ‘guess’ people’s passwords, starting with a dictionary

of words, place names, obvious numbers and so on. In other words, they try

lots of possible passwords until one works. This is called a brute

force attack, and the process is automated and fast — after all,

computers are ideally suited to such tasks.

Because of this, you’re encouraged to make strong passwords that

would take an impractically long time to guess. This doesn’t mean they need

to be so complicated you have no chance of remembering them, but on the

other hand, you should avoid single words or simple word–number combinations

like Sheffield123. One technique is to string together three or four random

words, like CorrectHorseBatteryStaple.

Meanwhile, phishing and

data breaches can expose your passwords to

nefarious individuals or the world at large. When this happens, the affected

password and account are said to be compromised.

For advice on dealing with this, see

Appendix: Secure a Compromised Account.

Not only might an attacker use compromised credentials to log into the

account in question, they might also try them on other popular websites.

This is called credential stuffing, and can be quite

successful because people often use the same password more than once.

To mitigate this risk, you’re encouraged to make a unique password

for each of your accounts.

Password managers

No one expects you to remember lots of passwords. Instead, it’s

recommended that you use a password manager, which stores

your passwords either on your device or in an online account that shares

them across all your devices.

Compared to a notebook, a password manager has several advantages:

- It can generate strong passwords for you, so you don’t have to think

them up yourself.

- Whenever you log into an account, it can automatically fill in the

appropriate password.

- It can help protect you from phishing, because it can’t be fooled into

filling in a password on a fake website.

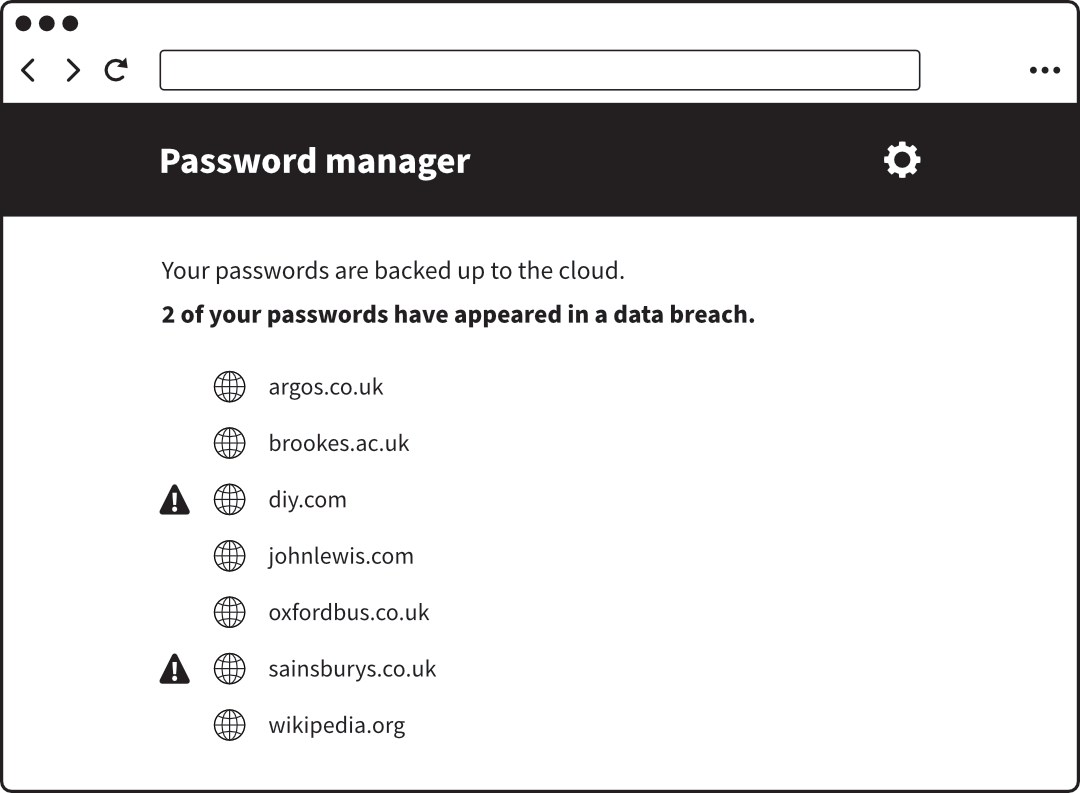

- It can notify you if one of your passwords appears in a data

breach.

A password manager built into a web browser

A password manager built into a web browser

Common concerns

If you have some doubts reading this, that’s normal. The idea that a third

party should store all your passwords, and that they should be random

gibberish you couldn’t remember even if you wanted to, is unnerving at

first:

- What if someone breaks into your password manager? It’s a valid

question, but by protecting it with

two-factor authentication – the

topic of the next chapter – you can make this effectively impossible.

- What if you lock yourself out and lose all your passwords? This would be

a nuisance, for sure, but over time you’d use the ‘I forgot my password’

facility to reset them all and build up a new collection.

It’s widely accepted that the benefits of a password manager outweigh the

risks. And this isn’t new advice: in a 2017 blog post, the UK government’s

National Cyber Security Centre wrote: “Should I use a password manager? Yes.

Password managers are a good thing.”

Choosing a password manager

The popular web browsers Chrome, Edge, Firefox and Safari all include a

password manager. The main advantage of using this is that there’s no extra

software to to install: you can view and manage your password collection

directly within the browser. If you use the same browser on all your

devices, you can sync your passwords between them via the relevant

account:

- Chrome uses a Google account

- Edge uses a Microsoft account

- Firefox uses a Firefox account

- Safari uses iCloud

To protect your passwords, be sure to enable

two-factor authentication on the

account. This is the topic of the next chapter.

If you work with a mixture of browsers or platforms, e.g. a Windows PC,

Apple iPad and Android phone, consider a dedicated password manager like

1Password, which works across all of them.

Using a password manager

After you start using a password manager, it typically collects your

passwords over time by asking ‘Would you like to save this password?’

whenever you log into an account.

If you’ve previously been in the habit of choosing ‘Never save

this password’, you’ll have built up a list of sites for which the question

is no longer asked. You’ll need to find and clear this list in order to once

again be prompted to save those passwords.

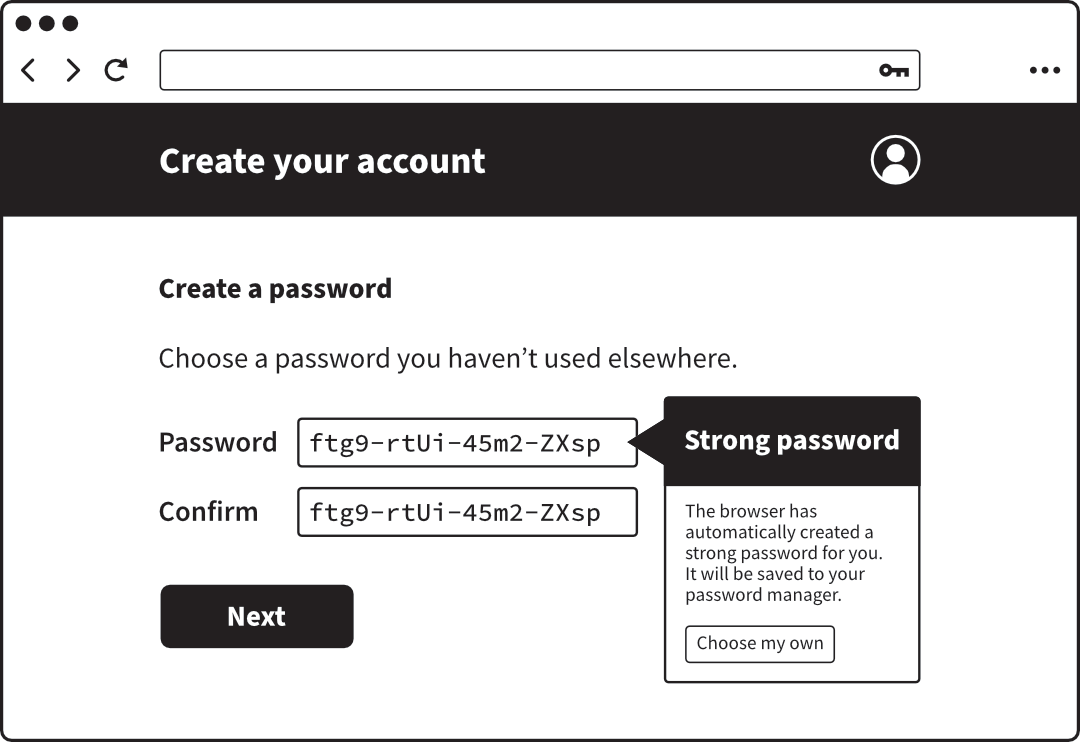

If you sign up for a new account, or go to change your password on an

existing account, this is the point at which the password manager can

suggest a long, random password for you. You don’t have to accept the

suggestion, but doing so gives you maximum security for minimum effort.

When you next need to log into the account, the password manager will fill

in the corresponding password automatically.

A password manager offering an automatically-generated password

A password manager offering an automatically-generated password

Forgotten passwords

When you create an account, the server holding your details does not store

your chosen password in a readable form. Instead, it derives a sequence of

letters and numbers called a hash from the password using a

one-way mathematical process. When you enter your password to log in, the

same process is performed and the hashes – not the passwords themselves –

are compared.

It’s a bit like mixing paint: combine several colours in specific

proportions and you’ll get the same new colour each time. But you can’t

unmix it: someone who’s only seen the new colour can’t work out which

original colours went in.

Storing hashes makes it much less likely that a nefarious third party, or

indeed a rogue employee of the company holding the accounts, can figure out

customers’ passwords in the event that the database is compromised. But it

also means that if you forget a password, there’s no way to retrieve it.

Instead you’re asked to make a new one, after proving your identity in some

other way.

Security information

To prepare for the possibility that you might one day lose a password, or

that a hacker might manage to break in and change it, you should provide

security information like your mobile phone number.

This is especially important for your email account, because email is

usually the key to resetting forgotten passwords for other accounts. In

other words, you should take very seriously the risk of losing access to

your email because so much else depends on it.

If the service allows you to give multiple phone numbers or alternative

email addresses, consider adding a trusted friend or family member too.

If you ever change your email address or phone number, be sure to update

these for all the services you use. It’s a tedious task, so consider doing a

few accounts each day. Your password manager is a good record of the various

accounts you have.

Beyond passwords

It’s now widely accepted that passwords alone, no matter how strong, don’t

offer enough security for modern times. In future, they might even become

obsolete in favour of something better. In the meantime, you can greatly

increase the security of your accounts using two-factor authentication and

passkeys, which are explained in the next two chapters.

What you can do

- Use strong, unique passwords. Avoid simple combinations of words, names

and numbers; and don’t use the same password for more than one

account.

- Use a password manager to make this easier. Protect the password

manager with two-factor authentication.

- Keep your security information up to date. It’s particularly important

that the email address and mobile phone number each company has for you

are correct, as these are the most common ways to prove your identity if

you get locked out.